Alina Martell is the pastry chef at Ai Fiori, Michael White’s contemporary Italian restaurant in New York’s Langham Place Hotel.

Tell us a bit about where you grew up?

I grew up in a town called East Lansing, Michigan. East Lansing is a great suburban town just outside the capital and the home to Michigan State University.

Both my parents also grew up in Michigan. My mother is Mexican American and my father’s family owned a dairy farm in southwest Michigan. I grew up with all kinds of good food. My mother cooked a lot and always had baked goods of some sort in the house.

How did you start cooking professionally?

After going to school at University of Michigan I initially worked in politics and law. I had always loved cooking and started out doing some catering on the side. A family friend worked part time in a bakery at one of the few nicer restaurants in the area. She said they were hiring and I decided to give a try. I realized I was having a lot of fun doing something I was good at. I knew I needed to train somewhere else so I came to NYC to go to school and to find a job.

Did you train in savory cooking as well as pastry?

I never trained formally as a savory cook but taught myself mostly from reading cookbooks and flipping through food magazines. When I first started cooking I used to plan dinner parties for friends and take recipes straight from the pages of Bon Appetit. I still enjoy savory cooking but I love pastry. To me pastry is just pure luxury, but an everyday luxury. You do not need it, but it is so much fun and so satisfying. I make a living feeding people sugar, but hopefully it is something that makes them happy.

What was your first restaurant in New York?

When I first got to New York, a friend from culinary school took me to wd~50 for a dessert tasting. I remember having Chef Sam Mason’s Manchego Cheesecake with an herb coulis and it was the most interesting dessert I’d ever tasted. A week later, never really having had a job in a serious restaurant kitchen, I walked in and dropped off my resume. I talked to a cook at the time named Bill Corbett, now the executive pastry chef for The Absinthe Group in San Fransisco. I just wanted to work there and they took me on as a stagaire. I worked at wd~50 just a few days a week but it was with an all star team of talent, including Sam, Bill and Christina Tosi. I was very fortunate to learn from all of them.

And then?

After finishing culinary school, I was hired by Johnny Iuzzini at Jean-Georges. I spent a few months working in Nougatine and then moved upstairs to the JG kitchen. I remember being a little bit terrified and completely overwhelmed. It is an intimidating kitchen.

It’s often said that Jean Georges is one of the most well run kitchens anywhere. Was that your experience?

Jean-Georges is a very well run kitchen. The food is beautiful and precise and the standards are very high. It is an awesome kitchen to train in. The pastry kitchen in particular was culinary school all over again. I think you never know how much you’ve learned from a place until you’ve left. In the midst of it, the kitchen is sometimes monotonous. Doing the same dishes over and over again. But at the end of it, or when you move on the to next kitchen you realize the amount you have learned is impressive.

And from there you went on to Corton?

Paul Liebrandt was getting ready to open Corton and had hired Robert (Bob) Truitt to be the pastry chef. Bob was a friend and I knew Paul through my husband. I know they were recruiting pastry cooks and needed help to open. At the time I was working at the French Culinary institute on a website called PastryScoop.com. I initially started at Corton a few days a week but eventually took a full-time job there. There was a pretty amazing staff of cooks and chefs that opened Corton. Every day there was a challenge in the best possible way. Paul is demanding but for good reason and I am incredibly proud to have just contributed.

And how did you come to Ai Fiori?

Bob was leaving to take the pastry chef job at Ai Fiori and there was a great opportunity at Ai Fiori, but in general at Altamarea Group. Michael White’s restaurant group was expanding. My husband, Amador Acosta, had opened Marea with Chef White with a lot of success. I knew it was a good group to join and that it would be a new challenge. We had always had a small, close-knit team at Corton, just two or three of us and a very modern particular style of desserts. At Ai Fiori it was going to be a crew of 7 or 8 doing breakfast, lunch and dinner 7 days a week in a dining room that could seat 160 people.

I’ve been here going on four years. Bob is now the executive pastry chef for AltaMarea Group. I have always had a great staff here. A lot of the pastry cooks have moved on to be sous-chefs and chefs at the other AltaMarea group restaurants. I think Ai Fiori is great training ground because of the scope of what we do. We do viennoiserie for breakfast, classic tarts and desserts for lunch like mille feuille and Paris-Brest, and modern plated desserts for dinner. We do a bit of bread production and have a great chocolate program. We get to practice everything.

And so, inevitably, when AMG is in the planning stages of a new restaurant I know Bob is going to take at least one of my cooks or sous chefs. I think that is what makes the program here at Ai Fiori and within AMG so great: there are always new challenges and opportunities for our staff.

What makes a successful composed dessert?

I think every chef has his or her own style. My style is influenced a lot by Bob and the sort of things we have been making for the past few years. I also think there should be an element of familiarity and surprise with dessert. For me creating dessert is always a balancing act.

At Ai Fiori we are able to do a lot within the frame of being a French-Italian restaurant, highlighting the cuisine of the Rivera. One of the classics here is our Ligurian olive oil cake. We have had it on the menu in some form since we opened. Sliced for breakfast, assembled with ice cream and fruit for lunch and as an element of a dinner dessert. Right now we have the olive oil cake on the dinner menu, layered with Sicilian pistachio, strawberry gelee and mascarpone mousse. Topped with fresh strawberries and a candied violet nougatine. The flavors—olive oil, mascarpone, pistachio—are all Italian but to me the dessert tastes like the perfect strawberry shortcake. It is not a complicated dessert, by no means all that innovative and the flavors are simple but it is one of my favorites.

We have freedom to play with what we create. We have a range of very classicly styled desserts with familiar flavors to desserts that are completely deconstructed. I like to have a vacherin on the menu and a lot of times we take apart the elements of a classic vacherin (sorbet, ice cream, meringue, etc.) and put it back together in fun ways. I saw a beautiful vacherin Michael Laiskonis did with a meringue that was formed in a ring and standing up on a plate. It was a bit of a high wire act to do for a busy restaurant like Ai Fiori but we found a way to make it work. Our dessert also included a pomegranate, green apple and lime. It ended up being a popular dessert I think in part because it was something surprising and interesting to see.

Is there one particular ingredient you’re excited about this moment?

We have a lot of fun with chocolate at Ai Fiori. We are fortunate to have a great relationship with Valhrhona. Recently we got in a single origin dark chocolate from the Dominican Republic, Loma Sotavento 72%. Valrhona made the chocolate in limited production and a portion of the sales benefit a school in the Dominican Republic near the cacao plantation where this chocolate is produced. We wanted to really showcase this particular chocolate so we designed a dessert around it. The dessert is a chocolate chiboust tart, baked to order. There is a bit of coffee infused into a ganache and chocolate covered candied cocoa nibs. Just to make it even more appealing we made a marsala gelato that we wanted to taste a like tiramisu—rich, lots of egg yolks and cream and a bit of coffee and marsala wine. It is a very satisfying dessert if you are a chocolate fan.

Your husband Amador Acosta is a Chef for Altamarea group (Chef/Kitchen Operations Director). Do you two cook at home much?

We cook a lot. Actually he cooks a lot. We probably stay in and cook at home five nights a week. My diet at work is not all that great and I know I consume far too much sugar, so we eat pretty healthy at home. Plus it is just how we like to eat. The usual is roasted chicken or a steak that we split, green vegetables and potatoes, a glass of wine and call it a night. I don’t do a lot of baking at home save the occasional pie or batch of cookies.

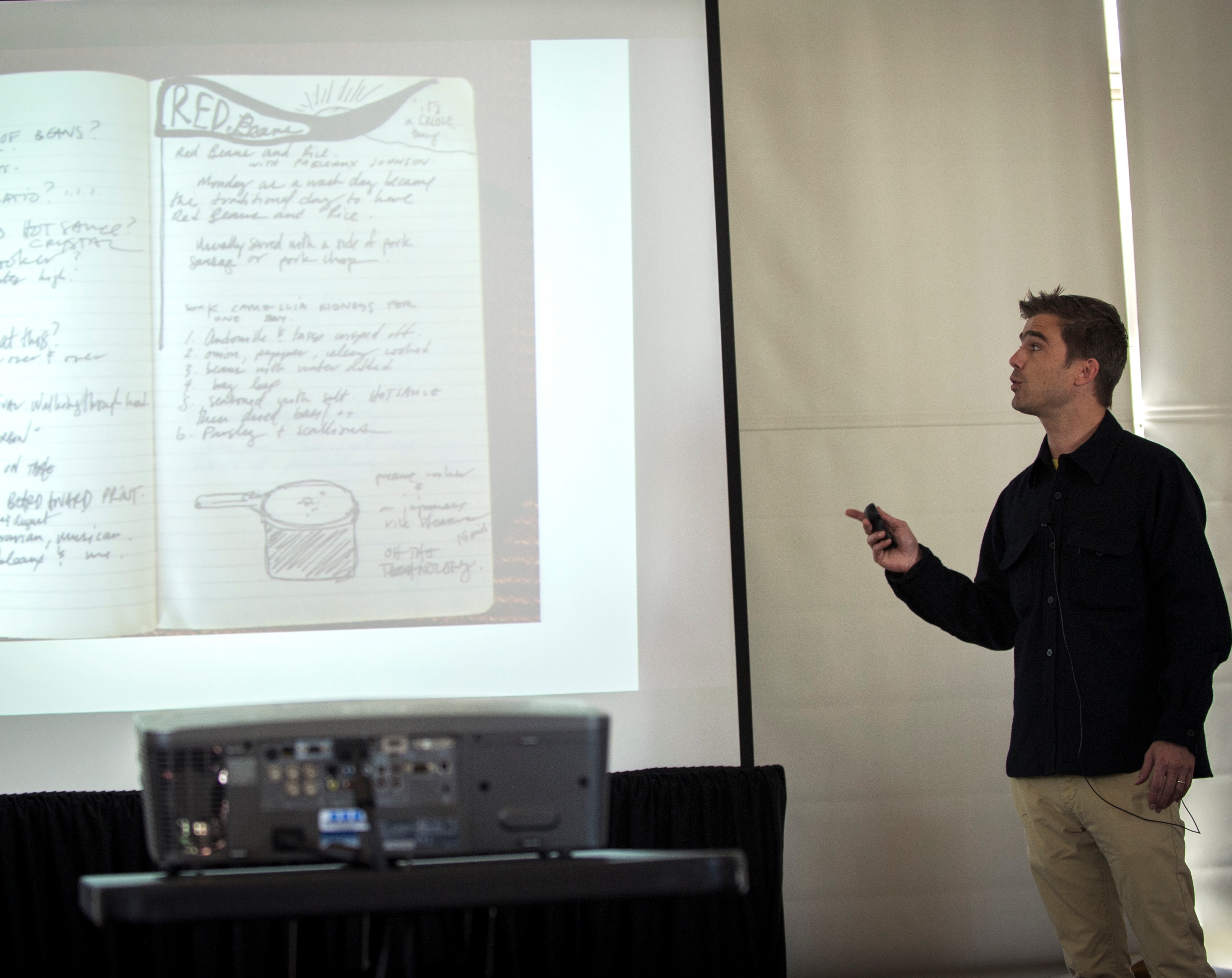

For some reason, or maybe because we both grew up in the midwest, we like canning and jamming. Come summertime when the good produce is at the Greenmarket we will start jamming everything. We are both big fans of peaches. Peach jam, peach pie, peach mostarda, peach anything.

Also love cherries. I have a friend whose family has an orchard in Northern Michigan, and they have these great cherries called balaton cherries. Balaton are like morello cherries, tart but with a dark flesh, so perfect for canning. If it is a good cherry season, they will send me a freight shipment from Traverse City. I hand them out to chefs and bartenders around the city. Bartenders like them because they’re good for making brandy or homemade maraschino cherries. Last year we got 100 lbs of balaton cherries straight from the farm.

Do you have any dining recommendations should we find ourselves in East Lansing?

There is as great restaurant that recently opened called Red Haven. One of the owners is a high school classmate, Nina Santucci. Initially Nina and her husband opened a food truck called The Purple Carrot that was a huge hit. I am very glad to see them and their restaurant doing well.