Matt Hoyle is the Executive Chef of Nobu 57 in New York, NY.

Can you tell us about where you grew up and your food influences? I grew up in the Northwest of England, in Lancashire. My grandparents cooked much more traditional English food, like offal and pigs’ ears, pies and stuff like that, which my mother really didn’t like. She made more continental than English food, but when I became older, I would then see it in restaurants, and it’s become a big thing again. It sort of skipped a generation or two. We kind of forgot it and then had to rediscover it as a nation of cooks.

How did you first get into cooking? After I finished school, I worked in two fish & chip shops in the town where I lived. I really liked food and cooking before that, but that was where I started to really enjoy the environment of cooking.

Who do you consider mentors? Obviously, Nobu-san has been a huge mentor, as well as Mark Edwards at Nobu London. Also, Terry Laybourne at 21 Queen Street in Newcastle. It was the only Michelin starred, fine dining restaurant in the northeast of England. I worked in his kitchen for three or four years, working and learning every section from larder to veg to sauce.

What attracted you to Japanese cuisine? I knew very little about Japanese food before I started at Nobu. In the North of England, it just didn’t really exist. The simplicity of the food really excited me. The technique is very precise. Knowing exactly what you want, whether it’s how you cut fish or how you cook it. I loved the food and it really spoke to me. Also, the way the kitchens were run was just different. The way Mark Edwards ran the kitchen in London was so different than any other kitchens I’d worked in. He allowed us to have a voice rather than knocking us down.

Are New York diners different than the diners in London? In general, London & New York are fairly similar cities. In New York though, you would have a full dining room and maybe two bottles of wine in the whole room at lunch time. In London, it’s more of a ‘let’s have another bottle before we go back to the office’. That European thing still exists there. The lunches are quite different.

What are some of the more popular dishes at the restaurant? We sell a lot of Japanese Wagyu beef. The quality of the Wagyu has come back better than ever after it was banned for a few years. Vegetable dishes are becoming more and more popular in their own right, not just as side dishes. Black cod is obviously still a best seller.

As a chef, what ingredients are you enjoying now?

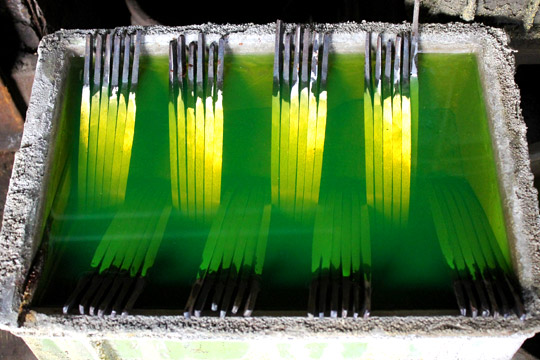

What are the essential tools you tell your new cooks they must have? A sharp knife. More of the cooks are using Japanese knives than they were eight years ago. I tell them they don’t need a full set, just start with one good chef’s knife. Learn how to sharpen it.

What are your favorites tools in the kitchen? For myself, I love plating chopsticks, but I don’t expect the cooks to have them. For kitchen equipment, it’s the Rational oven. It’s kept the restaurant open a long time. When all my other ovens break down, it keeps going and you can cook very precisely or overnight.

For young cooks starting out, what advice do you give them? You need a work ethic or you need to pick one up pretty soon. That’s essential.

Favorite places to eat in NY?

My wife is West African so we get a lot of West African food. There’s a place in Harlem called Ivoire, which is really good. For English pies, I like Harlem Shambles. They make Steak & Kidney, Cornish pasties, Aussie meat pies. For pork pies, Myers of Keswick is fantastic. They make everything in the back. My favorite for Japanese is Yakitori Totto.