People that are new to Japanese knives and even some more experienced users often have questions about what makes Japanese different and how the various knife shapes can be used. What follows is our simple guide on the most common knife types and their specific uses.

Gyutou / Chef’s Knife

Gyutou are the Japanese equivalent of a typical European chef’s knife. They are the ideal all-purpose kitchen knives and can be used for most tasks. Japanese gyutou are typically lighter and thinner than a European knife, are made out of a harder steel and as a result, hold a better edge. The design features nothing to obstruct the edge of the handle end of the blade, so it can be sharpened and thus used entirely. The word gyutou in Japanese means ‘beef knife’.

Santoku / Multipurpose

Santoku, which means ‘three virtues’ in Japanese, is an all-purpose knife with a taller blade profile than a gyutou. Its three virtues are the knife’s ability to cut fish, meat and vegetables. Santoku have a flatter ‘belly’ than gyutou and can be used comfortably with an up and down chopping motion rather than a ‘rocking’ type cut.

Sujihiki / Slicer

Sujihiki knives are the equivalent to a European slicer with a few differences. First, the blade is typically thinner and made out of a harder steel, allowing for better edge retention. Additionally, the bevel on the blade is sharpened at a steeper angle, allowing for a more precise cut. Sujihiki can be used for filleting, carving and general slicing purposes.

Petty / Paring

Petty knives are small utility or paring knives that are ideal for small, delicate work that a chef’s knife can’t handle such as delicate produce and herbs, small fruits and vegetables.

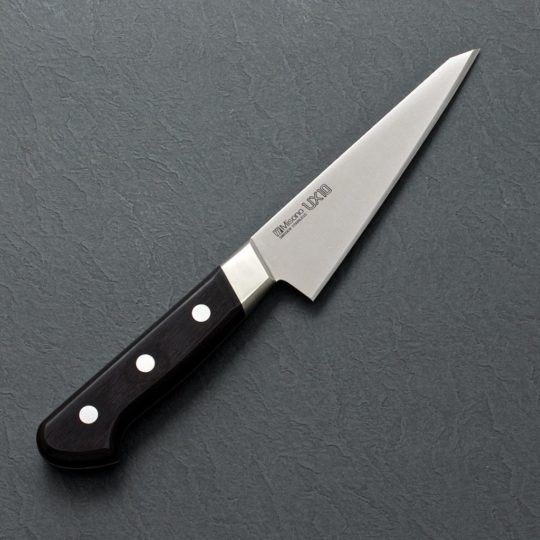

Honesuki / Boning

A honesuki is a Japanese boning knife and differs from its Western version, in that it has a triangular shape and a stiff blade with very little flex. The honesuki works incredibly well for deboning poultry and cutting through soft joints. Typically it has an asymmetrical edge, although 50/50 balanced versions (not favoring left of right handed use) exist. Due to its shape and height, the honesuki can also function nicely as a utility or petty style of knife.

Hankotsu / Boning

A hankotsu is a Japanese boning knife and differs from a Western boning knife in its shape. It has a thick spine and durable blade with none of the ‘flex’ found in a Western boning knife. Originally created to debone hanging meats, it is excellent at cleaning loins, but can function as a petty or utility knife on the fly.

Nakiri / Vegetable Knife

Nakiri knives are the double edged Western style equivalent of a single edged Japanese usuba knife. Thanks to their straight blade, nakiri are ideal for julienne, brunoise, allumette and other precision knife cuts for vegetables. Also a great tool for cutting into very hard skinned produce like pumpkins and squash.

Yo-deba / Butchery

Yo-deba knives are heavy, durable knives with a thick spine, which are used for fish and meat butchery. They typically feature a 50/50 balance so they are appropriate for both left and right-handed use.

Yanagi / Slicer

Yanagi are single-edged traditional Japanese knives used in a long drawing motion to cut precise slices of sushi, sashimi and crudo. Their single-edge means they are able get incredibly sharp.

Takobiki / Slicer

Takobiki are a variation of a yanagi and originated in the Kanto (Tokyo) region of Japan. They are also single-edged allowing for an incredibly sharp edge and are used for slicing sushi, sashimi and crudo. It is rumored that the blunt tip end was favored by sushi chefs in Tokyo because tight spaces meant they had less distance between themselves and customer, so the flat edge tip made for a safer experience.

Deba / Butchery

Deba are traditional single bevel Japanese knives with a thick spine and a lot of weight. They are used for fish butchery, filleting and can also be used on poultry. They are available in a range of sizes depending on the size of the fish or animal that is broken down.

Usuba / Vegetable Knife

The usuba is a traditional Japanese vegetable knife with a single edge. Single-edged knives are able to get incredibly sharp and are favored for precise vegetable work. The Kamagata Usuba, pictured above has a curved tip, which is a regional variation from Osaka.

Kiritsuke / Slicer

The kiritsuke is a traditional Japanese knife with an angled tip that can be used as either a sashimi knife or as an all-purpose knife. In restaurant kitchens in Japan, this knife is traditionally used by the Executive Chef only and cannot be used by other cooks.

Pankiri / Bread Knife

Pankiri are designed and used for slicing bread and baked goods. The ridged teeth are designed specifically for this purpose and can cut through hard crusts as well as delicate items without crushing.